Indigenous Inclusion: participatory approaches to conservation

Carrie E.T. Stiles

The author presents an ethnographic case study to explore how Garhwali farming communities from the Indian Himalaya experience participatory methods designed to conserve Plant Genetic Resources (PGR) and Indigenous Knowledge (IK). The study explores the problem of how to engage indigenous peoples in dialogue regarding conflicts arising from Article 27,5,3(b) of the agreement on Trade Related Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPs), which universally mandates life form patenting.

Note: See – The Life Patent, Convention on Biological Diversity and International Treaty on Plant Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture and TRIPS Article 27,5,3(b).

There are over 370 million indigenous peoples living in over 70 countries, the majority of whom live in poverty (IFAD, 2003 p. 5).

Indigenous peoples in poor countries are heavily dependent on seeds increasingly controlled by developing countries through the universal standardization of Intellectual Property Rights (IPRs) over Plant Genetic Resources (PGR) (Shiva, 2000).

However, indigenous peoples have not been included in stakeholder dialogues pertaining to the patenting of seeds.

Rather, they have been increasingly marginalized by Article 27,5,3(b) in the agreement on Trade Related Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS), which mandates the patenting of life forms.

This ethnographic case study explores the problem of how to engage indigenous peoples in dialogue regarding the universal standardization of life form patenting over PGR. The study answers the question, how do Garhwali farmers experience participatory approaches to the conservation of PGR and IK?

Data was collected through interviews and participant observation over six months in the Garhwal Himalaya. The study findings have been highlighted in three emergent themes including: experiences and strategies with participatory methods, the seed and a culture of sharing.

The study is intended to explore the potential for conflict transformation through participatory methods for biodiversity and IK conservation. Furthermore, the purpose of this study is to understand indigenous stakeholder’s experiences, perspectives and interests as a foundational premise for instigating dialogue.

The study was conducted from the perspective of Indigenous, Cultural and Farmers’ Rights, which specifically call for the participation of indigenous peoples’ in agenda setting, decision-making and policy formation (Tobin, 2009).

The field of conflict resolution (CR) has not focused on transforming conflicts arising from power imbalances pertaining to PGR patenting. The limited CR participation in addressing this specific, yet hugely consequential problem is regrettable because of the urgent need to engage peace scholars in engaging marginalized communities in inclusive dialogue on the global level. Existing studies of how to engage indigenous peoples in dialogue on this issue emerge from grassroots literature, anthropology, international politics and international rights in theory and practice.

Research methods

This study applies the ethnographic method to depict the ‘reality’ of indigenous lives by listening to the ‘voices’ of Garhwali people. Situating this ethnographic account in the context of IPRs over PGR is intended to shed light on divergent perspectives and power imbalances experienced by Garhwali farmers.

This study was designed to take into account local perceptions, institutions and collective action that allow farmers to conserve biodiversity and IK. Furthermore the research design was intended to explore various ethical questions regarding IPRs and cultural appropriation.

The primary source of data for this study was in-depth, semi-structured interviews.

The interview protocol consisted of a range of questions pertaining to participants’ experiences and perceptions of PGR and IK conservation. Participants were selected based on a variety of criteria. First, they were asked to participate if they were of Garhwali descent. Secondarily, they were asked to participate if they had experience with participatory methodologies for a sustained period of time.

Participants were also selected to depict perceptions over a relatively broad geographic range within the Garhwal. Twenty-five individuals composed the participant pool for this study. Interviews were conducted in both English and with a translator. English ability was not a condition for participation.

Processes

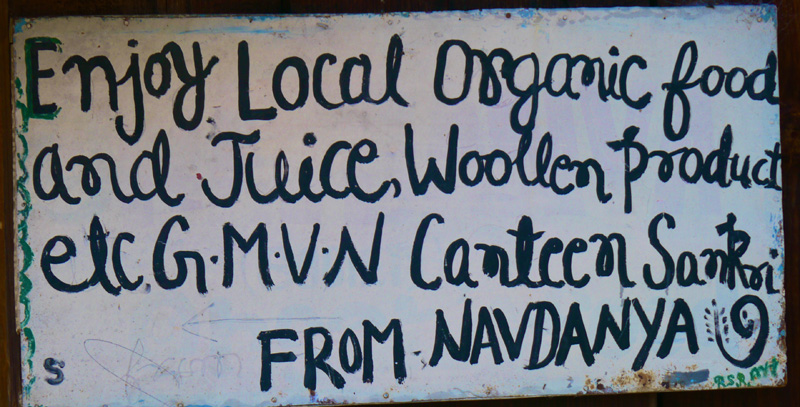

This ethnographic case study explores how Garhwali farmers experience participatory approaches to conservation implemented by the Non-Governmental Organization (NGO) Navdanya.

Navdanya is a participatory research initiative that gives guidance to environmental activists and also the largest fair-trade, organic network in India. Navdanya seeks to improve the wellbeing, and defend the rights, of small and marginalized farmers through participatory processes related to biodiverse organic farming and fair trade.

The organization’s grassroots coordinators engage local farmers through the creation of Self-Help Groups (SHG), mobilizing the local government (rural Panchayat), farmer trainings in biodiversity conservation and organic farming and as participants in various research projects and grassroots actions.

Navdanya has pioneered participatory approaches to transforming power imbalances in the global decision-making process pertaining to patents on seed. According to Navdanya’s (Navdanya, 2006) mission statement:

“Navdanya is born of a mission based on peace and non-violence… the human wellbeing especially of the poor and marginalised communities is directly dependent on the health and wealth of our biodiversity… We are therefore committed to resist patents on seeds and life forms promoted by the TRIPS agreement of WTO which leads to the privatization of biodiversity and the piracy of traditional knowledge…”

Navdanya has successfully challenged patents on Neem, Basmati and Wheat through the legal system.

Navdanya recognizes farmers as conservation experts and peace builders.

The NGO has empowered over 500,000 farmers through processes such as: community development projects, targeted trainings, educational programs, providing access to markets, fair prices and involvement in many special events, conferences, participatory research projects, protests and petitions.

Navdanya has organized over twelve hundred farmers meetings that tens of thousand of farmers participate in (Navdanya, 2006). Navdanya holds hundreds of training programs each year in which thousands of farmers participate. Navdanya also has converted over ten thousand farmers to organic methods each year, numbering tens of thousands of acres.

Through various Yatras (marches) hundreds of thousands of people receive Navdanya’s message.

Navdanya’s 54 community seed banks span 16 states in India and have provided impetus for the collection of thousands of varieties of seeds. Navdanya’s members can borrow seed for the season, but they must return seed of the same quality and in an amount exceeding the seed received to the village seed bank upon harvest.

Navdanya members are encouraged to bank local varieties in the community seed bank. Community seed banks build a stock of diverse seed varieties and provide farmers simple access to local seeds. Finally,

Navdanya introduced the mission of defending biodiversity as a commons by transforming hundreds of traditional Panchayats (democratic community committees) into Jaiv Panchayats as part of Navdanya’s Living Democracy movement.

Navdanya has pioneered a contemporary model of participatory research and development by replicating and enhancing pre-existing IK systems.

The model is rooted in dialogic relationship building and embraces indigenous institutions and the endemic culture of sharing. Navdanya’s methodology provides a model with features that could be replicated by other IK initiatives. The need for dialogues on IPRs over PGR is a central element of Navdanya’s grassroots initiative. Navdanya emphasizes local participation, local skills and local institutions as relevant forums for conflict resolution.

Understanding how this participatory process grows in the field highlights the gross inadequacy of unilaterally imposed decision making epitomized by the TRIPS agreement.

Actors and Setting

Surprisingly little information is available about Garhwali people.

What has been written is fragmentary and episodic. The Garhwal is an administrative division in the North Indian state of Uttrakhand (population 8.48 million) (Govt of Uttrakhand, 2011). The inhabitants of this region, and subject of this study, are from the ancient Garhwali ethnic group also known as Paharis (of the mountains).

The Garhwal state was founded in 823 AD and the Garhwal kingdom was founded in 1358 AD. The Garhwal kingdom continued in an uninterrupted like until being temporarily taken by the Gorkhas in 1803.

The British defeated the Gorkhas in the Anglo-Nepalese War (1814) and established the British Garhwal (1815) in the eastern half of the region. The heir of the Garhwal dynasty was granted the western half. The British were defeated through non-violent resistance in 1947.

The Garhwal Himalaya is sparsely populated (Dutta, et al, 2004).

Around 80% of the population lives in rural areas. There is very limited communication and many areas are not accessible. The severe agro-climatic variations, and other factors, result in a plurality of socio-economic lifestyles. However, most Garhwali people maintain a subsistence lifestyle. Most work activities are forest-based and there are 54,047 handicraft units in the state. Agriculture, cattle farming and a few cottage industries constitute the major part of the subsistence economy (Govt of Uttrakhand, 2011).

Garhwali people live in village communities.

Berreman (1999, p. 259) wrote that, “The community is the most relevant manageable unit of analysis if one’s aim is to achieve an over-all understanding of the way of life of the people in a limited time… Like all Indian villages, Pahari villages are not static isolated or autonomous.”

The local extended family is the basic economic, social, and religious unit. Garhwali communities have major settlements in about 3,580 small and medium sized villages located on slopes or in plain areas. The villages are often located near watercourses surrounded by agricultural fields. Garwhali villages maintain a traditional caste structure of labor distribution (Govt of Uttrakhand, 2011).

Agarwal highlighted the crucial axes of the ‘people-ecology’ interface in India:

I gradually realized that in a densely populated, poor country like India, people were dependent for their daily survival on the gross nature product, the benefit that nature gives them for free, rather than the gross national product. In India, no understanding of ecology can be complete without understanding the relationship between people and their landscape. This led me to see the interface between culture, people, and ecology. I could not understand ecology without understanding people, and I could not understand people without understanding their culture, including their religious faith. (2000, p. 171)

Shurveer Singh Rawat, Garhwali Panchayat leader from Sankrit village in District Uttarkhashi, expanded on Agarwal’s concept, “Garhwali is our local culture, our language, our dress are distinction. The natural environment influences and shapes our culture. The mountains can’t describe us, but it gives an indication” (interview by author, Uttrakhand, India, 15 Nov. 2009). Himalayan communities provide a dramatic illustration of the ‘people-ecology interface’. Thus, a description of the Himalayan environment is necessary to provide a holistic rendering of the Garhwali.

The ecosystem of the Garhwal Himalaya is incredibly distinctive.

Severe agro-climatic variations occur within a small geographical area (Dutta, et al, 2004). Forests, rugged mountains and high glaciers divided by narrow valleys, deep gorges and ravines characterize the Garhwal. Himalayan glaciers sustain seven of Asia’s most important rivers that provide water for hundred of millions of people (p. 13).

The Himalaya supports almost half of humanities ecological needs (40%) as the third largest body of snow on earth (Bhatt & Shiva, 2009, p. xi).

Study participants expressed serious concern about the impact of climate change in the Himalaya. Ghanshyam Prasad (interview by author, Uttrakhand, India, 5 Nov. 2009) commented on the devastating 2008 Himalayan drought,

“Water is the main problem, if we do not have water we cannot have farming. So the disruption to the water cycle has serious impacts.”

Vinod Chamoli (interview by author, Uttrakhand, India 10 Mar. 2010) echoed this concern observing that,

“The climate is changing very rapidly, snowfall is less, and rain is less. Chemical agriculture needs more water. When we talk about both systems: which is more beneficial?”

The Himalayas are under increasing threat due to climate change and the large-scale exploitation of natural resources.

Climate change is the most significant threat to the Himalayan ecosystem (Bhatt & Shiva, 2009, p. xi). Damage to the fragile ecosystem makes living conditions very difficult on even a subsistence level. Drought and other natural disasters are increasingly common occurrences and have a tremendous impact on the local populations.

Climate change has resulted in plant species moving to higher altitudes, alterations in plant flowering and fruiting behavior, erratic rainfall, decreased snowfall and the quick drying of perennial streams (Dutta, et al, 2004).

Balbeer Singh Rawat (interview by author, Uttrakhand, India, 19. Oct. 2009) also expressed concern. He explained that:

Many people know about the changing climate because of reduced snowfall and rain. In some places in the Garhwal Himalaya there is no water. We know this because we talked to people in the Climate Change Yatra this year…. On the march we talked with t villagers about how they now have to carry water long distances. Decreases in crop production and water are the major problems. In my village Sankrit, three years ago there were streams and in many places now the water has dried up. The women work more then the men, so the women have more information, so we were communicating with the women.

During the Yatra Navdanya collected information on the changing water cycle and agricultural conditions for a participatory study on climate change. Concurrently, Navdanya published the 2009 report Climate Change at the Third Pole: The Impact of Climate Instability on Himalayan Ecosystems and Himalayan Communities.

Results were publicized through Navdanya’s National Conference on Climate Change in the Himalaya (Bhatt & Shiva, 2009). The study found that biodiverse farming systems reduce vulnerability to drought and increase climate resilience.

The study also resulted in the drafting and presentation of a People’s Participatory Climate Adaptation and Mitigation Plan called the People’s Charter on Climate Change.

The participatory study qualitatively interviewed and quantitatively surveyed 755 people from Uttrakhand in 165 Garhwali villages from 2008-2009. The researchers also verified interviews by assessing the ground realities. Interviews and surveys were also were collected during the ‘Himalayan Climate Yatra (march)’ through three Himalayan states, which generated awareness amongst society at large.

The extensive study came to several conclusions (Bhatt & Shiva, 2009). The researchers findings for Uttrakhand include:

- a drastic reduction in snowfall

- glacial retreat

- disruption to seasonal rainfall

- the drying of springs and related drinking water crisis

- failure of agricultural crops

- increased forest fires that accelerate loss of animal and plant diversity

- rapidly changing forest structures

- displaced wild animal as a menace to agriculture

- reduced livestock due to depleted fodder and water resources

- the disturbance to seed formation due to temperature variation

The study emphasizes the connection between biodiversity conservation, reduction of climate change impact and poverty alleviation (Bhatt & Shiva, 2009, p. xii).

Biodiverse, local, organic systems reduce water use and risk of crop failure due to climate change in addition to producing more food and higher farm incomes. The priority of global trade for GMO corn, soya, canola and cotton increases climate vulnerability. Whereas production of drought resistant, local varieties of millets, that are nutritionally superior and use only 200-300 mm water, could produce four times more food that Green Revolution rice farming.

The People’s Charter on Climate Change was based on surveys and interviews collected at different altitudes and locations in five river valleys of the Garhwal Himalaya (Bhatt & Shiva, 2009). Thirty ‘veteran intellectuals’ or Climate Guardians (Ritu Praharies), six from each valley, were invited to participate to prepare a valley level climate adaptation and mitigation plan.

The five valley level plans were adapted into a People’s Charter on Climate Change for Garhwal Himalaya. The charter was given to the minister of environment and forests Shri Jai Ram Ramesh, the Ministry of Environment and Forests, Government of India and the Chief Secretary, Uttrakhand on September 6th, 2009.

Experiences with participatory methods

Study participants explained how they were personally transformed as a result of their engagement with participatory methods for biodiversity and IK conservation. Navdanya coordinators Dr. R.S. Rawat and Vinod Chamoli explained how their worldviews were transformed (interview by the author, Uttrakhand, India).

Previously, they endorsed industrial agriculture.

Now Dr. Rawat (5 Feb. 2010) engages farmers in dialogic processes that result in organic certification, research, conservation projects, procurement and management of grains, pulses and other food items. Chamoli (10 Mar. 2010) previously was the president of a cooperative society promoting industrial agriculture. He convinced the society to covert to promoting organic production after participating in Navdanya workshops.

Chamoli described the results of his personal transformation saying that, “At this young age they call me ‘the wise one’. The Panchayat have asked me to stand for election, but I do not want to enter politics. I want to continue as a grassroots community organizer.”

Another illustration of personal transformation comes from Coordinator Rukmani Rawat. She explained that:

Before I began working with Navdanya I was not that happy because my parents kept pressuring me to get married. In our religion there is a saying that a woman cannot take care of herself unless she is married. I told them even if I am not married I could take care of myself financially and mentally. After I started working they were very happy with me to see what I have done for my community. Now I am free to move around because my brother supported me for the good of my community, but this was not always the case. My brother said, ‘ I will support you in your cause.’ Now it is a ripple effect, people see what I am doing so they will allow the women to move freely. Now they can go where they like when previously they were restricted. (interview by the author, Uttrakhand, India, 5 Feb. 2010)

Rukmani, Dr. Rawat and Chamoli’s experiences reflect Lederach’s explanation that (1995) the pursuit of personal transformation and systematic transformation are not exclusive options. Rather, they are mutual and interdependent. Personal transformation and structural transformation must be pursued together to produce real social change.

Garhwali experiences with participatory methods have been life enhancing and are a source of pride in the community.

Navdanya coordinators from the Garhwal report having positively impacted their communities through relationship-based strategies. Study participants also explained how their social status improved as a result of their mobilization with Navdanya. Many also reported experiencing a greater appreciation for their culture and subsistence lifestyle as a result of grassroots engagement.

According to Shiva (2009) and Krishna (2009) participatory methodologies are the most effective method to mobilize from the grassroots and create sustainable livelihoods. Participatory approaches to transforming indigenous marginalization challenge existing hierarchical dichotomies.

Thamizoli (2004) explained that participation is a goal unto itself because the process is empowering. Through participatory methodologies at the grassroots level people become agents who define their own agenda and priorities.

The seed

“We may die, but the seeds must be left for the next generation.”

~ Navdanya Seed Keeper Bija Devi (interview by the author, Uttrakhand, India, 17 Mar. 2010)

Study participants explained how the free exchange of seed is integral for their survival and the conservation of biodiversity and IK. Understanding the significance of seed saving from the perspective of the Garhwali yields insights into the conflicts created through imposing IPRs over PGR.

Furthermore, understanding how farmer’s access genetic resources, how they exchange seed and how they improve local crop varieties reveal how participatory methods can counteract cultural and genetic erosion.

Study participant Anand Kumar (interview by author, Uttrakhand, India, 1 Feb. 2010) explained how Navdanya protects the ancient practice of seed saving. He remarks that:

Navdanya farmers all keep their own seeds. Seeds are also supplied from the Navdanya seed bank. The farmers are now self-sufficient in seeds through seed saving and an exchange amongst themselves. They don’t depend on the market. We discuss seed sovereignty with the farmers so they will keep seeds at home. It is best to keep your own seed so you can carefully check the quality – the quality of the seeds from the market is unknown

Participants highlighted the salience of seed sovereignty often during the course of research.

Balbeer Singh Rawat (interview by author, Uttrakhand, India, 19. Oct. 2009) explained that, “Saving seeds makes us self-sufficient, which is necessary for our freedoms so we do not go to others like a beggar.” Garhwali farmers report a feeling of increased security and well-being as a result of being self-sufficient in seed. Imported seed is viewed as injurious because it displaces local varieties and traditional practices.

From the indigenous perspective the seed is embodied culture, the symbol of life and continuity, thus it cannot be commercialized (Shiva, 2001, Shiva, 2005). Bhar and Shiva (2005, p. 167) that:

The seed, for the farmer, is not merely the source of future plants and food. It is the storage place of culture, of history. Seed is the first link in the food chain. Seed is the ultimate symbol of food security. Seed is sacred… Seed is the embodiment of the ideas and knowledge, of the culture and heritage of a people. It is an accumulation of philosophy, of tradition, of knowledge of how to work the seed… For the farmer, the field is the mother; worshipping the field is a sign of gratitude to the earth, who as mother, feeds the millions of life forms who are her children.

The seed and new crops are worshipped before being planted and consumed.

The festivals surrounding the agricultural cycle are integral to maintaining the foundational organization of society. The festivals symbolize the people’s intimacy with nature and that, “For the farmer, the field is the mother; worshipping the field is a sign of gratitude to the earth, who as mother, feeds the millions of life forms who are her children” (p. 168).

Indigenous peoples have developed sustainable livelihoods and PGR over many centuries through the practice of selective breeding. Selective breeding is to improve, adapt and evolve varieties by saving seeds that exhibit desirable properties such as drought, disease and pest resistance.

Local crop varieties can survive in a greater range of environmental conditions as compared to varieties distributed by corporate and government vendors (Bhatt & Shiva, 2009).

The break down of sustainable livelihoods occurs when farmers are forced to rely on costly external inputs and unable to adapt local varieties to rapidly changing weather conditions (Berson, 2010).

The increasing need to adapt to changing conditions in society, the environment and the market highlight the urgent need for biodiversity conservation (Pimbert, 1999). Dr. Rawat (interview by author, Uttrakhand, India ABCDEF) explained the significance of biodiversity and intercropping multiple varieties:

In the village of Sankrit they grow three or four varieties in a single field. If there is drought or two much rain there are different options. This is the security people have devised against climate change that comes from the community, not outside. Climate change means variability, not just drought. Last year in the month of March there was one or two day’s drastic temperature loss that affected our apple crop. There was a total crop failure in the state due to the sudden decrease in temperature. We need crops that are not susceptible to high fluctuation of temperature and moisture.

Traditional crops bred by farmers are the major source of traits for climate resistance. Study participant Rena Rawat further illustrates this point (interview by author, Uttrakhand, India 17 Mar. 2010) by described how the conservation of diverse plant varieties is vital to cope with the changing climate.

Forcefully imposed patenting laws require seeds to be sold with licenses that prohibit the act of seed saving among farmers. Syngenta chief executive officer (CEO) Michael Mack in April 2010 explained that,

“Farmers around the world are going to pay hundreds of millions of dollars to technology providers in order to have this feature [drought- tolerant maize] (ETC Group, 2010, p. 4).”

The licensing agreements and contracts that forbid farmers from using farm saved seeds have immense socio-cultural, economic and ecological repercussions (Siganporia, 2007; Shiva, 2005).

Study participants expressed disdain and alarm about the patenting of genetic traits required to adapt to climate change. Balbeer Singh Rawat (interview by author, Uttrakhand, India, 25. Oct. 2009) explained how Navdanya raises awareness about patents imposed by transnational seed corporations.

I have talked with the people about Monsanto that they want to steal our seeds and genetically take the traits and characteristics we have developed. I tell them that they should not take genetically engineered seeds. They ask me, ‘if they are destroying our seeds what can we do?’ We tell them to save the seeds. Many people know me because I am the only one who goes to talk to them about farming. They trust me and say, ‘you are the only person who cares about farming’. They do not trust in the government because they send pesticides with low prices trying to trick them. We have opposed many times the government distribution of internationally acquired seeds.

Likewise, Dr. Rawat (interview by author, Uttrakhand, India, 5 Feb. 2010) also comments on the negative impact of seed patent monopolies:

Seeds should not be commercialized by monopolies like Monsanto. The big corporations want to kill seed diversity for monetary benefit. To have this seed monopoly, they want to destroy the sustainable seed supply – so farmers have to buy their seeds.

IPRs over PGR increasingly impact the social institutions, cultural mechanisms and local production systems that provide access to and distribution of genetic resources through seed access and exchange (Siganporia, 2007; Shiva, 2005).

Eyzaguirre and Dennis (2007, p. 1496) explain the potential for injustice and ecological imbalance as a result of restricting farmer’s access to seed:

Plant genetic resources are still largely in the hands of the rural poor, as biological assets for their livelihoods. They are the raw materials that allow farmers to resist shocks and climatic variation. Although farmers’ assets can be enhanced by greater access to commercial germplasm, loss of access and rights to local germplasm takes power away from farmers and limits their contribution to future diversity and evolution in the plants and animals that sustain humanity.

Patents on seeds and the adjoining restrictions render the farmer both the source and the client in the chain of seed development (Shiva, 2002). IPRs ensure that the seed initially created by the farmer is sold back to her at higher prices as the property of the company that patents the seed.

Culture and sharing: the significance of relationship building

Garhwali farmers insist that community unity and strong relationships are necessary for prosperity, health and strategic problem solving. In the Garhwal Himalaya relationship building and reciprocal knowledge sharing are cultural and survival imperatives.

Participants explained how the right to share is a problem-solving strategy expressed through prioritizing relationships.

Understanding the socio-cultural and political significance of common property, embodied in the free exchange of seed, and cooperation is crucial to evaluating the cross-cultural impact of imposing IPRs on indigenous peoples.

The traditional practice of seed saving, use and exchange exists within the socio-cultural ethic and practice of sharing. Free seed exchange represents the reciprocal exchange of ideas and knowledge as recognition of interdependence. Seeds and knowledge are shared reciprocally to maintain continuity in relationships in farming villages, with nature and expand outwards to benefit the ecosystem (Brush, 2007).

Dr. Vandana Shiva explained the significance of relationship building and culture in the Garhwal.

She replied:

The beauty of Garhwal is that, because it is a mountain region, it still has elements of what I would call a nature’s economy functioning. And in nature’s economy everything is in the commons: the seed is in the commons, your forest is in the commons, the water is in the commons. That is the legacy we built on. All conflict comes out of trying to own in divisiveness what belongs to everyone in the common good. By holding in the common good, the seed the biodiversity, the communities of Garhwal are able to understand much more quickly what the alternative to privatization is…

and

They have a very strong community spirit, and that is what we built on because Navdanya’s philosophy is based on saying patents on seeds and patents on life are wrong. Biodiversity and seeds are in the commons and they belong to the community. It is not something you have to teach from outside. We have to help people remember this, and that remembrance then becomes the basis of creating perpetual peace (interview by the author, Uttrakhand, India, May 1st, 2009).

Garhwali culture is imbued with spiritual, philosophical and practical appreciation for the right to share through a firm belief in the commons.

Navdanya Coordinators Balbeer Singh Rawat (interview by author, Uttrakhand, India, 19. Oct. 2009) and Ghanshyam Prasad (interviews by the author, Uttrakhand, India, 5 Nov. 2009) emphasized the significance of community unity where everyone is embraced as one family. Prasad says, “All problems can be solved when you share them.” Balbeer explained that Garhwali communities thrive and depend on relationships.

Chamoli (interview by the author, Uttrakhand, India, 10 Mar. 2010) also commented on the strength of the Garwhali community saying that,

“When problems arise the people unit to help one another. For example, if someone is injured the community will collect money and donate it to get the injured person to the hospital. Later this favor will be reciprocated.”

Additionally, Shurveer Singh Rawat (interview by the author, Uttrakhand, India, 15 Nov. 2009) explained that the Garhwali mentality is premised on the right to share knowledge. Garhwali cultural values are deeply intertwined with the community’s daily existence and functioning in the mountains and tied to the mountainous environment.

The Garhwali knowledge system is maintained and transmitted through community cooperation and an ethic of sharing.

Rukmani Rawat (interview by the author, Uttrakhand, India 5 Feb. 2010) explained the seminal need for relationships to transmit knowledge,

“Knowledge passes through generations. If someone is unwell grandmothers prepare a concoction and her daughter will watch and learn. Maintaining these relationships is important to pass down knowledge. One mother is everyone’s mother and one auntie is everyone’s auntie.”

Likewise, Bachnidevi Thalwan (interview by the author, Uttrakhand, India, 15 Mar. 2010) commented on the role of sharing in conserving IK, “The unique feature of Garhwali culture is sharing: We teach our children when they are young that they should share and help when others are in times of need and Rukmani Rawat teaches the small children also.”

The ability of indigenous peoples to conserve, recover, develop, and transmit their inherited knowledge is contingent upon a traditional worldview that promotes an ethic of sharing.

Practices that promote reciprocal knowledge sharing and sharing of resources are present throughout indigenous cultures. The WHO (2001) explained that, “most members of traditional and indigenous communities were -and probably still are- very generous in sharing their knowledge.” However, IPR regimes are fundamentally incongruent to the ethic of sharing and reciprocity typical of indigenous cultures because they promote exclusive rights and monopoly control through exclusion.

Conclusion

This study captures the perceptions, practices and experiences of indigenous, Garhwali farmers as they seek to transform conflicts through participatory processes.

The Garhwali example shows that indigenous survival requires cooperation, reciprocal knowledge sharing and a participatory approach to biodiversity and IK systems whereas IPRs over PGR deny local people vital participatory agency. Indigenous peoples have not benefited from the commercialization of genetic resource.

Rather, patents on seeds impact their basic needs and livelihoods because limiting access to PGR results in genetic erosion, erosion of local environmental expertise and biopiracy. However, limitations to monopoly control over biological resources can be accomplished through the recognition and inclusion of indigenous communities and participation at all levels of decision-making and management.

Seeking to understand the actual experience of people who are silenced, oppressed and marginalized has multiple implications. Sen (2009, p. 130) emphasized that:

We do not live in secluded cocoons of our own. And if the institutions and policies of one country influence lives elsewhere, should not the voices of affected people elsewhere count in some way in determining what is just or unjust in the way a society is organized, typically with profound effects – direct or indirect – on people in other societies?

Sen (2009, p. 409) explained that patent laws are one of several issues that are, “…eminently discussable issues which could be fruitful subjects of global dialogue, including criticisms coming from far as well as near.”

Understanding the experiences, perspectives and interests of Garhwali farmers is necessary for the functioning of a legitimate dialogue in the interest of conflict transformation. Garhwali farmers are crucial to developmental methodologies because they are experts in their fields, long-term participant observers and knowledge subjects.

Their vital experiences, interests and perspectives on conservation must be included in the global decision making process on the future of food and seed for a living democracy to flourish.

thnx carrie for all dis ! nd im so happy dat u did it at my village saur sankri….nd u remind me of my grandfather he ws a great man ,,,,,,,,,

good work